Why Israel Won’t Take the Win

Plus: AI ‘suicide race.’ Biden’s Taiwan blunder. Would Trump concede? Big Tech goes nuclear. And more!

Two big things happened in the Middle East this week—big even by the standards of the past year: 1) Israel finally managed to kill Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, the prime mover behind the October 7 attack on Israel. 2) The US finally put boots on the ground in Israel. It sent 100 soldiers, along with a missile defense system they’ll operate in the event of another Iranian ballistic missile attack, which is expected to ensue if Israel follows through with plans to retaliate for the last one.

The first development raised hopes that the second one would prove superfluous—that the expanding Middle East conflict might now be wound down, and those anti-missile missiles might not be needed after all. With the death of Sinwar, wrote Matt Duss of the Center for International Policy in The New York Times, “the United States and its partners have a window to halt the downward spiral to regional conflagration.” The US, he said, should push hard to end the Gaza war, get the hostages released, and forge a ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon. And “in furtherance of those aims, the Biden administration should also urge Israel to refrain from potentially escalatory strikes on Iran.”

The logic makes sense on paper. The death of Sinwar creates an opportunity for the Israeli government to declare victory in Gaza—and to sell that declaration to the many Israelis who felt that justice wouldn’t be done until the architect of October 7 paid the ultimate price. And Israel’s recent blows against Hezbollah—the killing of its leader and the destruction of much of its arsenal—provide a chance to say mission accomplished on that front, too. And what’s the great urgency about striking Iran? Iran’s regional military strength has been sapped by the decimation of Hezbollah, and Tehran had signaled an aversion to direct conflict with Israel even before that.

Meanwhile, the wave of Israeli euphoria over Sinwar’s death gives Netanyahu fresh political capital, possibly enough to survive a clash with hardliners in his coalition who will press for continued war. So maybe, if Biden finally uses his full leverage as Israel’s arms supplier, he can compellingly argue that, as he put it at an earlier juncture, Netanyahu should “take the win.”

But there’s little chance that much of this will happen, and this week’s second big development—the deployment to Israel of that American anti-missile battery—helps explain why. The deployment symbolizes with particular power the longstanding tendency of America’s Israel policy to create what economists call “moral hazard.” The basic idea is that being shielded from the adverse consequences of your actions can encourage risky behavior.

Trita Parsi of the Quincy Institute argued in Zeteo this week that Biden has over the last year repeatedly provided such shields for Israel. Whenever Netanyahu escalates the conflict—by, say, invading Lebanon or bombing Iran’s embassy compound in Syria or assassinating (relatively moderate) Hamas leader Ismael Haniyeh on Iranian territory—Biden “rushes to defend Israel from the consequences of its own escalation,” Parsi writes. The result is to encourage more escalation.

The Biden administration has argued that this “bear hug” approach allows US policymakers to influence, and sometimes restrain, Israel. But evidence for that argument is sparse. As Biden has continued to arm Israel and defend it on the world stage—and has helped it fend off two rounds of missile strikes from Iran—Netanyahu has opted to expand the war. Parsi writes: “Had Biden refrained from adding additional defensive capabilities to Israel after it needlessly intensified the conflict, the cost of escalation would have been higher for Israel—perhaps even prohibitive.”

Biden officials might argue that they pulled off a successful bear hug this week. Media reports suggest that agreeing to send the missile defense system to Israel, along with those 100 troops, played a role in getting Netanyahu to agree that in striking Iran he will avoid particularly sensitive targets, like nuclear facilities and oil refineries.

At least: Those targets won’t be hit this time around. But Netanyahu knows that Tehran will feel compelled to respond forcefully to any powerful Israeli strike, so he can assume there will be a next time. And, with US troops in Israel, he can then feel even more confident than he otherwise would that America will help him deal with blowback from a strike on Iran’s refineries or nuclear facilities. Moral hazard.

The US, Parsi argues, has strong incentives to change course. One is that Iranian missiles could kill US soldiers. If that happens, America could find itself drawn deeply into an intensifying and expanding war. (Of course, from Netanyahu’s perspective, direct American involvement is a feature, not a bug. And note that it could further heighten moral hazard.)

Another incentive for the US to abandon the bear hug strategy, writes Parsi, is the impact the conflict is having on America’s global standing. While the Biden administration says it’s building a global system in which international law carries weight and “universal human rights are respected,” its closest ally is prosecuting a war that, in the eyes of much of the world, violates those principles.

Of course, Israel’s global standing, too, has suffered from its conduct of the conflict, and will continue to suffer. But many Israelis feel that the world just doesn’t understand the neighborhood they live in, or what it takes to survive in that neighborhood—so low global standing is a price they’ll have to pay to keep surviving.

And it’s true that many international observers view Israel’s strategic situation differently than Israel does. They view it as ultimately non-zero-sum. They think Israel can only get truly enduring security if things also improve for various nearby actors. That certainly includes the long-suffering Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. But it also includes Iran, whose leaders feel that their country is vulnerable to aggression by both Israel and the US and that they need deterrent proxy forces like Hezbollah to stay safe.

Of course, this non-zero-sum view could be wrong. But so long as Israel gets uncritical military support from the US, and can be shielded from the consequences of its more zero-sum view, Israeli leaders won’t have to even consider the possibility that their view could be wrong. That’s a big moral hazard.

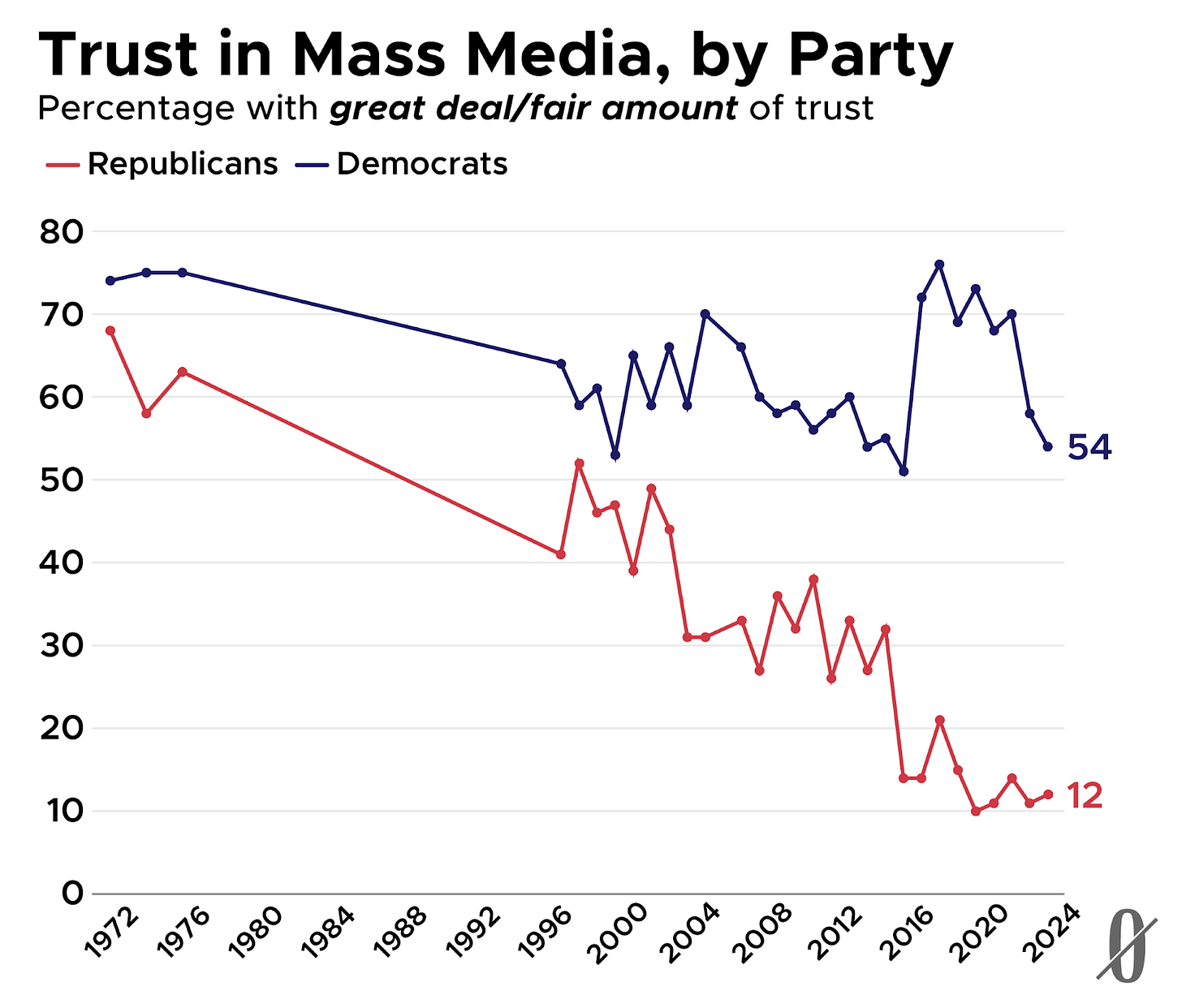

The longstanding gap between the amount of trust Republicans and Democrats place in the media is narrowing—but only because Democrats are joining Republicans in losing faith in it.

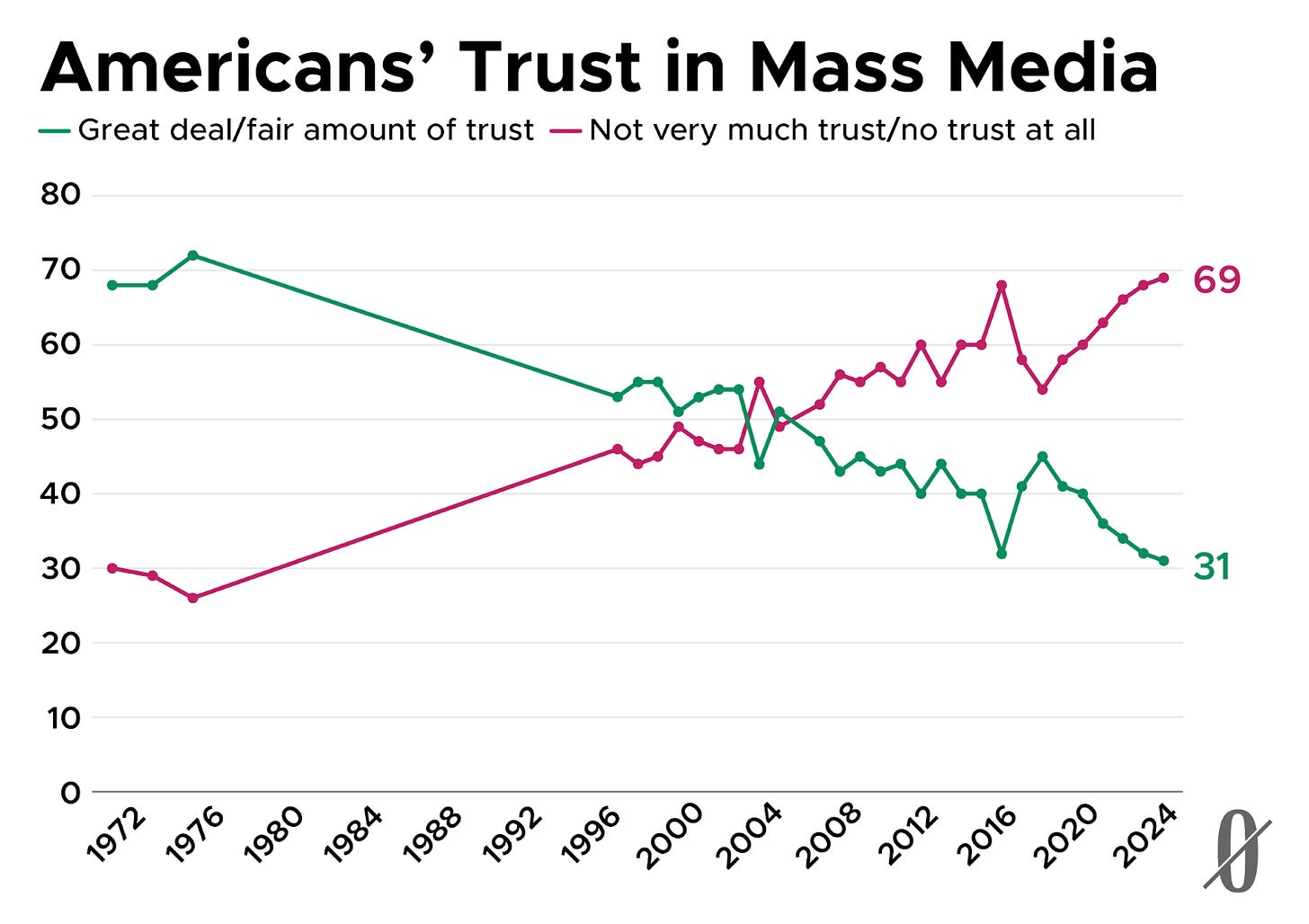

A new Gallup survey found that Americans have historically low levels of trust in the mass media “when it comes to reporting the news fully, accurately and fairly.” Only 31 percent of US adults said they trusted the media a “great deal” or “fair amount”—the lowest total in the poll’s 52-year history. Thirty-three percent said they had “not very much” trust in the media, and 36 percent had “none at all.”

While Republicans have long viewed the media with more suspicion than Democrats, the partisan divide widened dramatically in 2017, when Donald Trump became president. That year, Democrats’ confidence in the media spiked to 72 percent, while the Republican number held steady at 14 percent. Since then, Democrats’ confidence has dropped to 54 percent, narrowing the gap.

Even if present trends were to continue and erase the divide entirely, that wouldn’t necessarily signify a convergence of perspectives. Democrats and Republicans presumably tend to distrust the media for different reasons. Republicans may hate the New York Times for going too hard on Trump, and Democrats for not going hard enough.

One question the Gallup poll didn’t illuminate is how NZN readers feel about the mass media. So tell us: How much do you trust the media?

Only one in four registered voters believes that Donald Trump will accept the results of next month’s election if Kamala Harris wins, according to a recent poll from the Pew Research Center.

The survey shows a sharp divide along partisan lines. Ninety-five percent of Harris supporters believe their candidate would concede if she lost the election, while only four percent believe Trump would do the same. Among Trump supporters, 48 percent say Harris would accept a losing result, while 46 percent believe that Trump would do so.

All of which leads to this week’s NZN Metaculus question: Will Donald Trump concede if he loses the 2024 presidential election? (For a refresher on what we’re doing with Metaculus, check out last week’s Earthling.) Head over to Metaculus to submit your answer. We’ll close the question on Wednesday. (And we’ll accept the results!)

Now for last week’s results: According to the NZN braintrust, there is a 15 percent chance that Israel will strike an Iranian nuclear facility before the US presidential election. So NZN readers are expecting a less eventful month than NZN managing editor Connor Echols, who put the odds at 40 percent. (NZN staff writer Andrew Day tried—and failed—to calm Connor’s nerves in the members-only Overtime segment of last week’s Earthling Unplugged.) If you think Connor’s estimate was a bit too hair-on-fire, feel free to assuage his fears in the comment section below.

A pillar of America’s China strategy—restrictions on Beijing’s import of microchips—is making an invasion of Taiwan more likely, according to Paul Triolo, an expert on Chinese tech and a partner at the Albright Stonebridge Group consulting firm.

Triolo’s argument begins with Taiwan’s dominant role in the global production of microchips. The Taiwanese company TSMC manufactures 90 percent of the world’s most advanced chips, including chips designed and sold by American companies like Intel and Nvidia. China’s reliance on TSMC’s output had long served as a “silicon shield” for Taiwan, Triolo argues; the likelihood that the TSMC factory would be enduringly disabled in the event of war deterred a Chinese invasion.

But the US “chip war” against China, begun by President Biden two years ago and aimed at China’s AI sector, is eroding that shield. By limiting China’s access to advanced chips sold by Western companies, Biden has reduced China’s dependence on the TSMC factory and so reduced the disincentive to invade Taiwan (which Beijing views as a renegade province). Meanwhile, says Triolo, the chip war has also spurred China to build up its indigenous capacity to make advanced chips, thus reducing the future potency of the economic weapon Biden is wielding.

This worry that Biden’s chip war could lead to real war is one that, actually, has been advanced for some time by noted worrier (and NZN EIC) Robert Wright. But Triolo is the first expert NZN has found who validates this anxiety. As it happens, his validation came to our attention during a recent Wright-Triolo podcast conversation. NZN members (aka paid subscribers) can watch the moment when Wright and Triolo both discovered that there are twice as many people worried about this problem as they’d thought—which is to say, a total of two. (The magic moment comes early in the members-only Overtime segment.)