George Bush’s Time Bomb Goes Off

Plus: AI just got smarter. Swing states judge Trump’s foreign policy. Gaza and US interests. Bob vs. Bloom on Musk vs. Brazil. Crypto-powered sanctions busters.

Note: Don’t forget to check out Earthling Unplugged, Bob’s conversation with NZN staffer Andrew Day, on the Nonzero Podcast feed.

This week, as another anniversary of the 9/11 attacks passed, we at NZN were tempted to defy the prevailing spirit of solemn remembrance by complaining about the Bush administration’s reaction to the attacks: Instead of heeding the advice of wise elders, and reflecting on how human nature can lead people to counterproductively overreact to provocations, the Bush foreign policy team chose to invade not one but two nations—and disaster ensued.

However, we’ve decided not to complain about this momentous blunder by Bush’s neoconservative team. Instead we’ll complain about a different momentous blunder by Bush’s neoconservative team: America’s withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in June of 2002, midway between the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Believe it or not, the consequences of that move could prove worse than all the mayhem abroad and terrorism at home that has resulted from the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Withdrawing from the ABM Treaty raised the chances of both nuclear war and war in outer space. A pair of analyses posted this week explain why.

First, in Responsible Statecraft, Ben Chiacchia, a strategic analyst and US naval officer, makes an underappreciated point: though the ABM treaty had focused on limiting defensive capabilities—missiles poised to attack incoming ballistic missiles—some of these defensive missiles, with a bit of fine tuning, could do a good job of shooting down satellites. So the ABM Treaty wound up putting a damper on the development of anti-satellite weapons (ASATs).

Bush’s withdrawal from the treaty ushered in an era of ASAT development and testing by the US, Russia, and China. Within six years, all three countries had generated lots of space debris by smashing their own satellites with missiles. General Chance Saltzman, Chief of US Space Operations, last year called the first of these smashings, China’s 2007 ASAT test, a “pivot point” in the militarization of outer space. Chiacchia would say the true pivot point was five years before that.

As Chiacchia notes, the last country that should want to trigger an anti-satellite arms race is the country that has the most assets in outer space—which is to say, the United States. He calls the withdrawal from the ABM treaty “an unforced error that now holds in peril significant military and civilian space-based infrastructure.” Hence the “growing chorus of alarm in Washington” about dangers in outer space—threats to American assets and threats to the very usability of orbital space (including the dreaded cascading debris proliferation of the “Kessler effect”).

Another thing Washington is alarmed about is Chinese nukes. The New York Times recently reported that President Biden has approved a “highly classified nuclear strategic plan” that “reorients America’s deterrent strategy to focus on China’s rapid expansion in its nuclear arsenal.” This week, during a podcast appearance, Lyle Goldstein of Defense Priorities (and formerly of the Naval War College) traced the roots of this expansion to, among other things, the withdrawal from the ABM Treaty.

The ABM Treaty had been grounded in the logic of mutually assured destruction:

So long as all nuclear powers know that nuclear war would bring unacceptable devastation to their country, none of them is tempted to launch a first strike. And all of them, thus reassured that the chances of being hit by a first strike are remote, are less likely to feel a need to expand their nuclear arsenals (and less likely to put those arsenals on a hair trigger alert). However, a country with enough ABMs to fend off all or almost all incoming nukes might be tempted to launch a first strike—a prospect that, however hypothetical, could encourage that country’s adversaries to build more nukes so they can overwhelm the ABMs and make that first strike less tempting. And so on: an endless offense-defense arms race.

Hence the wisdom of the ABM Treaty: strictly limit the number of ABMs a country can have and so preserve the logic of mutually assured destruction, thus reducing the incentive of nuclear powers to expand their nuclear arsenals (and also reducing the baseline level of tension).

After Bush withdrew from the ABM treaty, Goldstein notes, China and Russia “were really sounding the alarm… They were alarmed because that really began to put their arsenals at risk, meaning they could no longer have assured destruction potential.”

This didn’t lead to an immediate nuclear buildup by either country. For one thing, other arms agreements—notably START and the INF Treaty—remained in effect for a time. And Goldstein isn’t saying the ABM Treaty withdrawal is the only factor that contributed to the current Chinese nuclear arms buildup. Nor is Chiacchia saying that this withdrawal is the only cause behind the current militarization of outer space.

But in both cases, withdrawal from the ABM Treaty raised the chances that there would be trouble down the road. And the hoped-for upside of the treaty—that the US could be made safe from nuclear attack—never materialized, owing to what a naive hope that was in the first place. And now the trouble down the road is here.

A new survey of voters in swing states brings some encouraging results for advocates of foreign-policy restraint—and some head-scratching ones for advocates of ideological coherence.

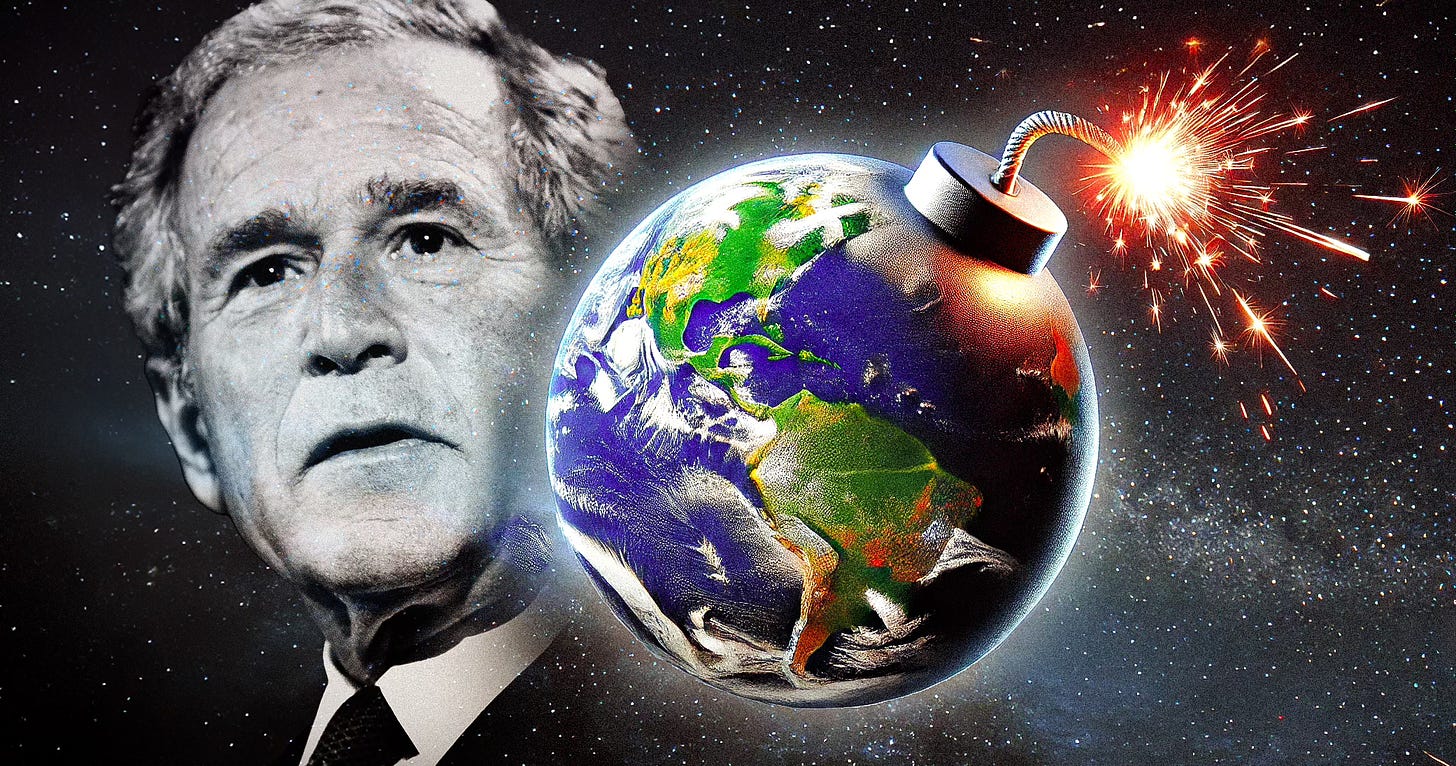

The pro-restraint Cato Institute, in collaboration with YouGov, surveyed voters in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. Most respondents said: 1) the US is too involved in foreign conflicts; 2) the US should play a “shared” global leadership role, not a “dominant” one; and 3) there should be an “immediate ceasefire” in Gaza.

So far, so coherent. But:

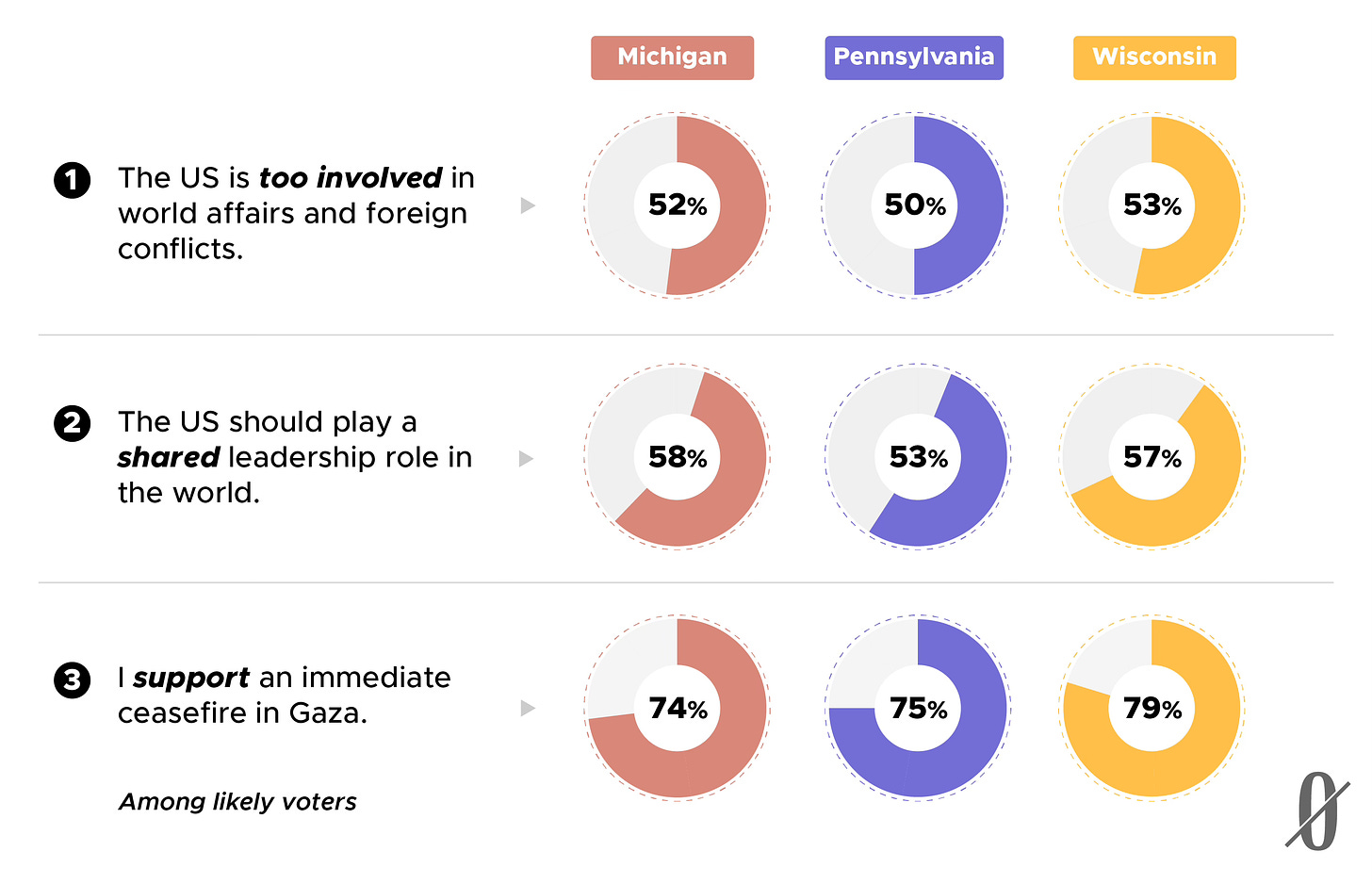

Though majorities in all three states preferred Trump on foreign policy and said he’s more likely than Harris to keep America out of foreign wars, majorities also said he’s more likely to drag the US into World War III. And, evidently, that wasn’t considered a very remote prospect; most respondents said they believe the US is “closely” approaching a third world war.

Attempting to make sense of all this, Cato writes that voters may distinguish between “what a candidate says about policy and how they perceive that candidate’s judgment and impulsivity.” But why would concerns about Trump’s judgment and impulsivity loom larger in the World War III question than in the foreign wars question?

NZN readers, if you think of ways to resolve this apparent tension, please leave your theories in the comments.

OpenAI this week released a long-rumored large language model (code named “Strawberry”) that, the company says, is trained to spend time “thinking through problems” before generating output and so is better at reasoning than its ancestors. Early reviews suggest that, though the model has shortcomings, and is in some ways inferior to existing LLMs, it does represent the biggest advance in language-generating AI in more than a year. (Unless, maybe, you count advances in “multimodal” AI, but those are more about the integration of audio and video into LLMs than about reasoning power or the quality of linguistic output.) The new model was greeted with praise by AI enthusiasts and with concern by AI safety activists, who highlighted some alarming behavior on its part.

The model is called OpenAI o1, and it clearly surpasses other LLMs in both formal reasoning (like math) and less formal reasoning; it can handle word games that often flummoxed other LLMs, like advanced crossword puzzles and acrostics and Wordle. And it’s better at figuring out how to get a person, two chickens, and a fox across a river in a boat of limited capacity without the fox eating any chickens—a species of puzzle that sometimes elicits comically stupid answers from LLMs.

OpenAI o1 also sets a new high water mark for performance on science exams. And it is much better at handling complex planning than past models, according to Ethan Mollick, a respected AI watcher who has given all the major LLMs a workout. But Mollick, who wrote a book about AI called Co-Intelligence, seemed unsettled by the degree of autonomy he witnessed. The model does “so much thinking and heavy lifting, churning out complete results, that my role as a human partner feels diminished,” he said. “Sure, I can sift through its pages of reasoning to spot mistakes, but I no longer feel as connected to the AI output, or that I am playing as large a role in shaping where the solution is going. This isn’t necessarily bad, but it is different.”

AI safety advocates flagged behavior they found troubling, such as deviousness; in one case, when given a quantitative goal to reach, the LLM decided to manipulate data to create the illusion of success. And it seems to be more likely than past models to help someone figure out how to build a biological weapon or steal a car.

But there’s lots of upside, and some people have very high hopes for where this lineage of LLM will lead. Noam Brown, an OpenAI researcher who worked on the new model, said, in reference to the fact that it has to think for seconds or even minutes before responding to some queries: “But we aim for future versions to think for hours, days, even weeks. Inference [computing] costs will be higher, but what cost would you pay for a new cancer drug? For breakthrough batteries? For a proof of the Riemann Hypothesis?”

Mollick concluded his assessment of the new AI with this thought:

As these systems level up and inch towards true autonomous agents, we're going to need to figure out how to stay in the loop—both to catch errors and to keep our fingers on the pulse of the problems we're trying to crack. o1-preview [the version of OpenAI o1 he tested] is pulling back the curtain on AI capabilities we might not have seen coming… This leaves us with a crucial question: How do we evolve our collaboration with AI as it evolves? That is a problem that o1-preview can not yet solve.

This week psychologist Paul Bloom came on the Nonzero podcast and talked about the Trump-Harris debate, the latest Tucker Carlson outrage, and many other topics. One of those other topics was Elon Musk’s beef with Brazil—a subject that sparked a lively debate between Bob and Paul.

Some background: A Brazilian Supreme Court justice ordered the suspension of Twitter service after Musk resisted taking down right-wing accounts allegedly spreading misinformation. After Twitter (or, technically, X) refused to pull its own plug, the judge mandated that internet service providers block access to the social media site. But Starlink, Musk’s satellite-based internet company, refused to comply.

Starlink eventually relented, but Bob was still a bit unsettled by the way Musk was trying to throw his power around (given that Brazil is a sovereign nation that, like the US, doesn’t give foreign billionaires the right to override its rules). Paul’s sympathies were more with Musk, on grounds that issues of free speech were at stake. Below is a (lightly edited) transcript of the beginning of their debate.